If you're exhausted in more ways than one, it's probably affecting your cognitive abilities, emotional stability, and physical performance. At Fatigue Science, when we talk about fatigue, we’re talking about cognitive fatigue. This mental fatigue leads to reduced alertness, reaction time, and effectiveness—all of which manifest in the form of sub-optimal physical performance.

Mental Fatigue Meaning

Mental fatigue occurs when you get inadequate sleep or when sleep and activities fall outside of our biological need to consistently sleep at night and be active in the day—it’s not the same as fatigue resulting from physical exertion. Mental tiredness can happen because you're getting poor sleep and have accumulated a sleep debt or when you're working night shift outside of your natural circadian rhythm, for example.

This leads to cognitive and physical effects of exhaustion. What happens mentally when you don't sleep for 24 hours for example? Mental fatigue leads to reduced alertness, reaction time, and effectiveness—all of which manifest in the form of sub-optimal physical performance. These symptoms of mental fatigue are different from the symptoms of physical exhaustion.

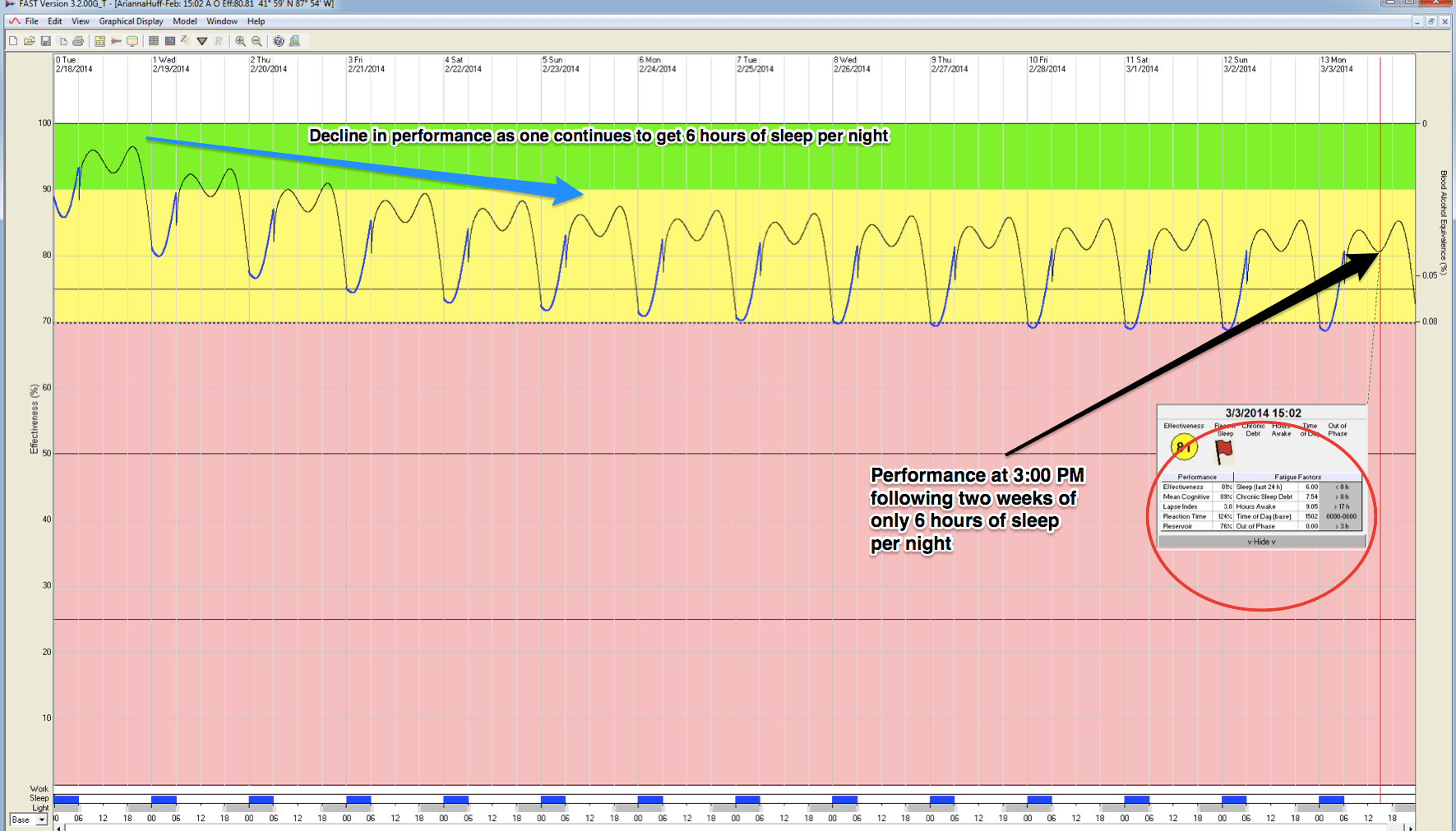

Those who routinely obtain less than 7-9 hours of uninterrupted sleep per 24-hour period will have a high homeostatic drive for sleep as the body struggles to restore balance. Getting only six hours of sleep a night isn't enough. In addition, scheduling inconsistencies often lead to a high circadian drive for sleep at exactly the wrong times of day as well as to sleep-initiation problems at night.

Symptoms of Physical Fatigue

Physical effectiveness, or energy, is different. It’s a function of non-sleep and circadian-related factors such as the type, intensity and volume of exercise (or physical labor) as well as muscle fiber composition, neuromuscular characteristics, high energy metabolite stores, buffering capacity, ionic regulation, capillarization, and mitochondrial density.

Physical energy can be viewed as the capacity to perform a certain amount and intensity of physical activity for a given period of time. Elite athletes, for example, who routinely engage in high-intensity training, are far less susceptible to physical fatigue than those who are sedentary. They run faster, lift more weight, and perform for longer periods of time due to their enhanced physical conditioning.

Physical vs Mental Fatigue

Mental and physical energy are governed by very different underlying processes—they’re separate biological functions. Having said that, they can coexist. So what's the difference between mental vs physical exhaustion?

If you're physically exhausted due to high-intensity physical activity, you may struggle to run, lift, or play, but your alertness and concentration will remain intact. In fact, most research concludes that physical activity has either a positive effect or more often, little or no impact on mental performance.

However, when a person’s mentally exhausted due to sleep deprivation, their alertness will suffer while most aspects critical for physical performance will be preserved. And while sleep loss affects mood, motivation, judgement, situational-awareness, memory, and alertness, it doesn’t directly affect cardiovascular and respiratory responses to exercise of varying intensity, aerobic and anaerobic performance capability, or muscle strength and electromechanical responses. But, time-to-physical-exhaustion is shorter and their perception of exertion and endurance is distorted.

Even though the symptoms of physical fatigue have little to no impact on mental alertness, the reverse is true—mental fatigue has a great deal of impact on the physical. There are physical effects of mental tireness. This is how a competitive decline takes root under conditions of sleep loss.

Which Is Worse? Physical or Mental Exhaustion

Between physical and mental fatigue, mental fatigue is worse for your health. It puts your health, safety, and performance at risk. It can have profound impacts on your mood, productivity, and emotional health. The cognitive and physical symptoms of mental fatigue are worse overall than physical fatigue.

Learn more about the differences between mental and physical fatigue in this comprehensive eBook, The Science of Sleep. DOWNLOAD NOW.

References

Effects of physical activity and inactivity on muscle fatigue

Bogdanis G.C. (2012)

Neurocognitive Consequences of Sleep Deprivation

Durmer J.S., Dinges D.F. (2005)

The Effects of Physical Exertion on Cognitive Performance

Krausman A.S., Crowell III H.P., Wilson R.M. (2002)

Cognitive methods for assessing mental energy

Lieberman H.R. (2007)

Sleep deprivation and cardiorespiratory function. Influence of intermittent submaximal exercise

Plyley M.J., Shephard R.J., Davis G.M., Goode R.C. (1987)

Investigating the interaction between the homeostatic and circadian processes of sleep–wake regulation for the prediction of waking neurobehavioural performance

Van Dongen H.P.A., Dinges D.F. (2002)

Sleep deprivation and the effect on exercise performance

VanHelder T., Radomski M.W. (1989)