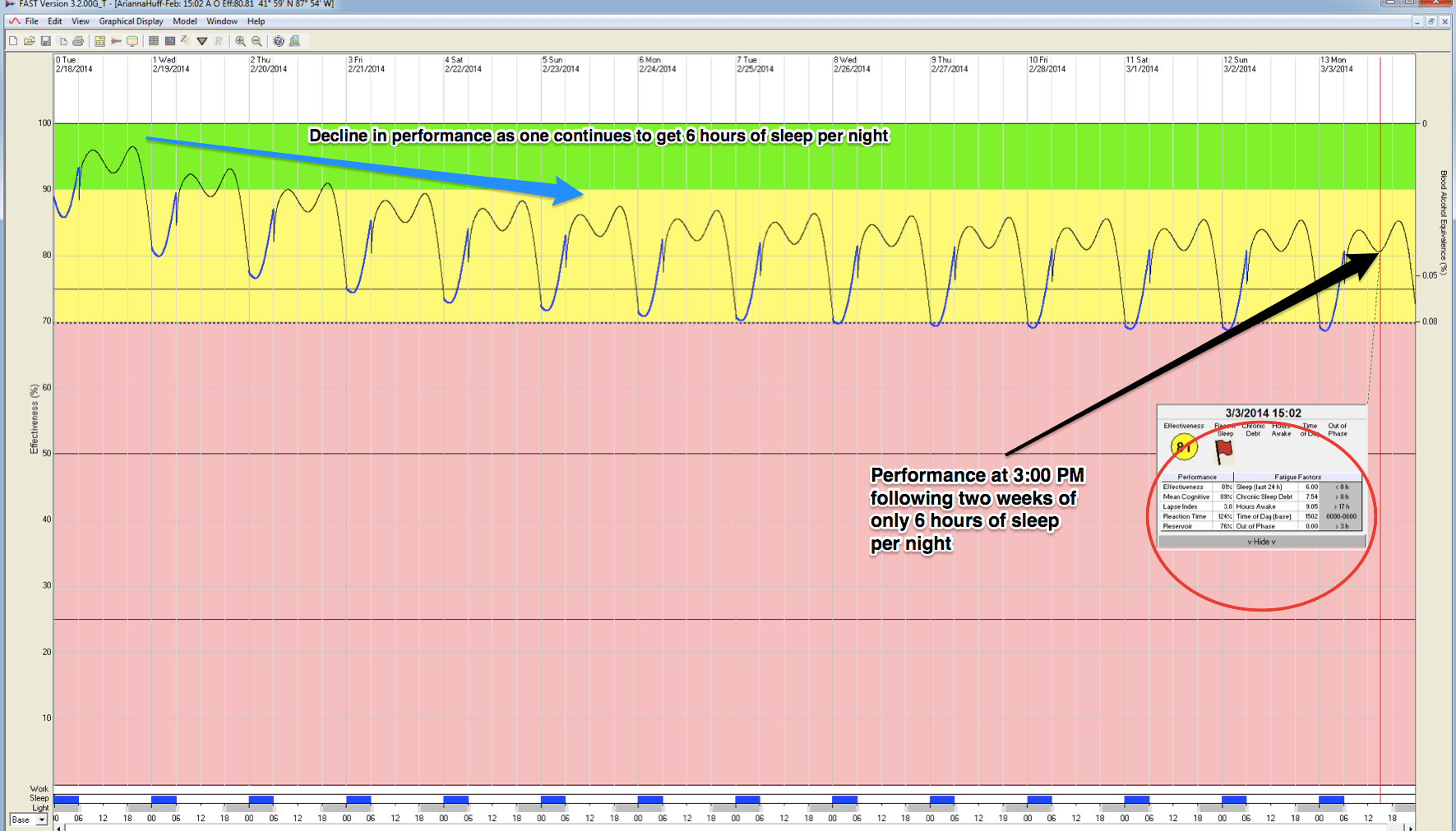

Although the science of sleep is a relatively new field (most of what we know about sleep has been learned in just the past 50 years), studies continue to show that failure to obtain adequate and consistent restful sleep is associated with attention deficits, memory problems, mood disturbances, and impaired mental performance. In fact, chronic sleep loss of 2-4 hours per day for 2 weeks has been found to degrade performance to the same extent as 24-48 hours of total sleep deprivation!

Unfortunately, 40% of Americans get less than the recommended 7 hours per night. This, of course, includes professional athletes whose insufficient sleep leads to alterations in carbohydrate metabolism, appetite, food intake, and protein synthesis—all of which stand to reduce athletic performance, particularly during events that require prolonged physical endurance. Peak competitive performance can only occur when an athlete’s sleep is optimal.

And yet, recently published data on Australian elite athletes suggest that a majority of team sport athletes have no strategy in place to overcome poor sleep. While coping with stress, jet lag, and demanding schedules can present challenges for even the most dedicated athletes, sleep in almost any circumstance can be improved by following these 10 steps toward better sleep hygiene.

1. Stick to a consistent wake-up and bedtime every day of the week

While many believe sleeping in on the weekends is a luxury that should not be missed, this habit creates body-clock disruptions that can turn into chronic sleep problems.

Someone who wakes up at 5:00 am on most days, but sleeps until 9:00 am on weekends, is readjusting their body’s internal clock for 2 days every week.

The delayed wakeup time leads to later daylight exposure and an alteration in one’s sleep drive, which will ultimately push back the next sleep period. Come Sunday night, sleep initiation at the proper time is difficult to achieve, and when the alarm clock sounds early Monday morning, the body is determined to sleep another hour or two. As a result, you fall ‘out of synch,’ and fatigue-related moods, lack of alertness, and performance problems arrive.

2. Use the bedroom only for sleep and sex

The bedroom should only be used for activities that are compatible with sleep. Even during travel periods, it is possible to create better sleep-conducive mental associations with your sleep arrangements. While certain sleep-environment and game-timing factors may be beyond your control, everyone can avoid playing computer games and using mobile devices in the bedroom.

Athletes need to be particularly wary of using technology within an hour of going to bed. Research suggests that electronic media exposure enhances alertness due to the bright light emitted by phones and computers, melatonin levels suppressed by TVs, and because the content presented on these devices is engaging and exciting. Bottom line, sleep and technology in the bedroom don’t mix!

3. Resolve daily dilemmas outside of the bedroom

Dealing with ‘worry issues’ outside of the bedroom can be tough for anyone who is striving to excel in sports. However, there are some simple techniques that can help minimize the time spent lying awake in bed thinking about tomorrow or worrying about what happened earlier today.

First of all, it’s important to be honest with yourself and recognize whether you are a worrier. If so, before going to bed, make a ‘worry list,’ and write a brief action item beside each concern. This can eliminate the temptation to make important decisions or plan new activities when your focus should be on falling asleep. Allow yourself a sense of closure each night by writing down your concerns and possible solutions, and then physically lay them aside.

4. Establish a bedtime routine

Engaging in a pre-bedtime routine is beneficial for several reasons. Remember, humans are creatures of habit, and once well-learned sequences of behaviors are established, one action usually automatically stimulates the next. Because of this, it is important to adhere to a consistent nightly routine whenever possible.

An example would be to turn off the TV at 9:00 pm, take a hot shower, lay out workout clothes for the next day, read a relaxing book for 30 minutes, set the alarm clock, and go to bed by 10:30 pm. This sequence will prepare the body and brain to fall asleep at the desired time each night. Keep in mind that habits are relatively easy to establish, but difficult to break. Thus, if your bedtime practices have involved behaviors not conducive to sleep, it will take some time to break these connections and reestablish a positive routine.

5. Create a quiet and comfortable sleep environment

A quiet, cool, dark, and comfortable sleep environment is crucial for the best possible sleep. Although complete environmental control is difficult to accomplish, especially when traveling, everything that can be controlled should be controlled. Make sure the room is dark with a comfortable temperature (around 67 degrees F is best). It’s better to have the room slightly cooler than normal with enough bed covers to stay warm.

Unwanted noise can be masked with a fan or other noise-cancelling device. Aim to keep surrounding sound levels steady, low, and consistent. Earplugs are also helpful for attenuating outside noises, although it may take up to a week to get used to sleeping with these. Finally, make sure the mattress and pillow are firm and supportive. If not, replace them.

6. Don’t be a clock-watcher

This caution is especially vital for someone who is already worried about their sleep. Watching the clock sets up a maladaptive pattern of thinking: You wake up for a few seconds, but instead of just going back to sleep, you look at the clock thinking, ‘it’s already midnight and I’m still not sound asleep!’ Then you start to worry, ‘what if I don’t fall asleep again soon’, and so on. This can rapidly escalate into a full-scale waste of time in futile worry.

Knowing what time it is will not improve the quality of sleep, it will not make it easier to go back to sleep, and it will not increase the amount of available sleep time. So, don’t do it!

If necessary, place your alarm clock on a table that is out of reach, and make sure it is facing away from you. Resolve to just go back to sleep whenever brief awakenings occur. Even if it’s only 15 minutes before your alarm will go off, 15 extra minutes of sleep is better than 15 minutes of worrying, any day!

7. Don’t consume caffeine within 4 hours of bedtime

Caffeine is no-doubt the primary energy booster among athletes because it works and most of the time there are no prohibitions against its use. However, we know that caffeine exerts a negative effect on sleep quality if taken too close to bedtime. While the advice is to avoid any caffeine within 4 hours of bedtime, a recent scientific paper indicated that even morning caffeine consumption can negatively impact nighttime sleep.

Be sure to consider the possibility that you may be consuming caffeine in unassuming products. For instance, certain brands of orange soda, varieties of tea, chocolate, and many over-the-counter pain-relieving medications contain caffeine. In order to avoid stimulant-induced sleep problems, take the time to understand caffeine’s effects and carefully review all food, drink, and medicine labels that could potentially contain this compound.

8. Don’t use alcohol as a sleep aid

Though many athletes avoid alcohol altogether, some are tempted to use it from time to time as a ‘sleep promoter.’ While it is true that alcohol makes most people sleepy, and therefore increases the speed of sleep onset, the problem with beer, wine, and cocktails is that they disrupt the foundational structure of sleep, particularly during the second part of the night.

The negative impact of alcohol on sleep quality combined with its effects on next-day blood-sugar levels makes it a bad choice for anyone seeking optimal competitive performance. So, if you do choose to drink, avoid consuming alcohol within 4 hours of bedtime.

9. Don’t take naps during the day (if you have trouble sleeping at night)

Daytime napping can be a wonderful way to compensate for inadequate nightly sleep opportunities. However, if there are chronic sleep problems due to poor sleep habits, napping during the day should be avoided for one simple reason: Napping is sleep, and sleep of any length decreases the body’s drive for sleepiness. This means that a nap during the day will inevitably make it harder to fall asleep at night. Thus, someone who is already experiencing nighttime sleep problems should avoid this added complication by foregoing daytime naps and opting for an earlier bedtime instead.

10. Get out of bed and go to another room if sleep does not arrive in 30 minutes

Just as it takes time to build strength, endurance, and athletic skill, it should come as no surprise that overcoming years of poor sleep conditioning requires patience, adaptability and a positive attitude. As you wait for noticeable improvements to occur, it’s important to avoid lying in bed awake for more than 30 minutes each night waiting to fall asleep. This advice also holds true for those who normally sleep soundly, but occasionally experience problems.

When sleep does not come readily, get out of bed, go into another room, and engage in some type of quiet activity (like reading or listening to music) until feelings of sleepiness return. At this point, go back into the bedroom and try again. If, for some reason, a second or third attempt does not work, try sleeping on the couch in another room.

Although there will be bumps along the road, remember that following these steps toward better sleep hygiene will eventually produce desired results. As the saying goes, anything worth having is worth waiting for, and quality sleep is no exception.

In U.S., 40% Get Less Than Recommended Amount of Sleep: Hours of sleep similar to recent decades, but much lower than in 1942

Jones JM (2013)

The effects of sleep extension on the athletic performance of collegiate basketball players

Mah CD, Mah KE, Kezirian EJ, and Dement WC (2011)

Understanding sleep disturbance in athletes prior to important competitions

Juliffa L, Halson S, and Peiffer J (2015)